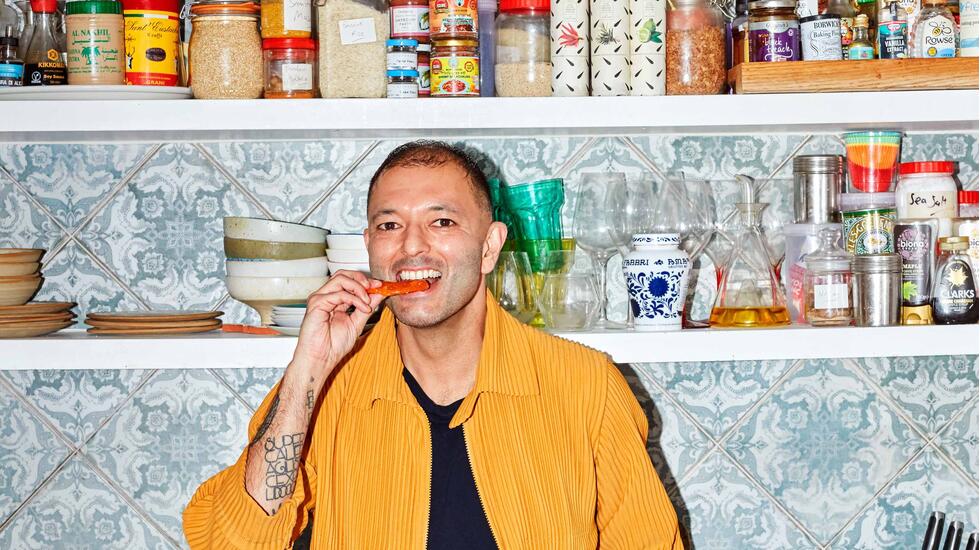

The food writer, whose debut cookbook Mother Tongue is out now, talks Indian supermarkets, culinary identities, and boldly flavoured fried chicken sandwiches

21 March, 2023

Gurdeep

Loyal answers the phone after enjoying two lunches. The

first, a Calabrian chilli pulled pork, was a test recipe for a food

magazine that had him dipping into the pan as he cooked. The second

was a simple soft-boiled egg sandwich – a Loyal take on old-school

egg and soldiers.

Twisting up traditional dishes is something of a signature

kitchen move for the food writer, who has just published his first

cookbook. Mother Tongue: Flavours of a Second Generation

is a creative collection of recipes intertwining Loyal’s British

and Indian heritage with the flavours and ingredients he’s

encountered through work, travel and the kitchen tables of his

friends. Mixing up Punjabi spices with British roasts and Japanese sandwiches, the recipes are as

vivid as the book’s neon-pink, paisley-patterned cover. Even the

intellectual introduction – which smartly opines that preserving

food culture should be a fluid, ever-changing process – is anything

but pious. The writing is as warming as the cooking itself, which

includes iterations of curried roast chicken, black pepper-roasted

strawberries and saffron-infused custard tarts.

Here, Loyal chats about his signature cooking style, how travel

can shape our palate, and why visiting a local Indian supermarket

will open up a world of new flavours.

I was born in Leicester into a very big Punjabi family. I’m a

second-generation British Indian, and for any Punjabi, food is the

rhythm of our lives.

I’ve always been interested in the idea that as a

second-generation British Indian immigrant, I’m an amalgamation of

my mum and my dad, but also myself, by being British by birth.

When I’m at home, or I’m cooking for friends, I mix up all the

flavours of everything I’m encountering in the world and pair it

with my own British Indian identity. My friends used to say, “why

don’t you write about this?”, so I did.

Gurdeep Loyal, left, and bitter gourds for sale in a British

Indian food store. | Photo credit: Matt Russell

It’s incredible to look back at people’s heritage through food,

but I’m more interested in what is happening now. What’s the next

step? What’s the next part of the story? When cuisine travels, what

happens to it? For my family, this cuisine travelled from India and

Punjab to Britain, and then I’ve taken it elsewhere and added to

it. This hybrid cuisine is an expression of my identity through

food. I’ve eaten my way around the world and discovered that there

are as many culinary narratives in the world as there are people,

and what’s exciting is to allow people to frame their own culinary

narrative via their own perspective.

I’m against the idea of there being culinary boundaries. People

will look at my cooking and say, “well, that’s not British food”,

or, “that’s not Indian food”, and I’ll say, “no, it’s British

Indian”. I call it third-culture cuisine. I am British and I am

Indian, and I am an amalgamation of both. I don’t feel people

should be locked into any ideas of authenticity because everyone’s

story – and their food – is authentic to them.

“Multicultural” as a word is often used as a checkbox exercise

in the food world. For me, the idea of a concept being

intercultural is more interesting – it has more depth, and it’s

about cultural exchange. In my book – and with my cooking – I want

to encourage people to get out to the diaspora-run food stores in

their community, whether it’s an Indian supermarket or a Greek

deli. I’ve got loads of friends who say, “there’s a Vietnamese

store at the end of my road and I don’t want to go in because I’m a

bit scared”, and I always say, “go in and see what’s there. I

guarantee you will come out with two or three things that will

amplify your pantry into 1,000 different directions”.

Guimarães, left, and a Cretan honey stall. | Photo credit:

Toms Auzins / Shutterstock.com

I often make the miso-masala fried chicken sandwich. Who doesn’t

love a fried chicken sandwich? The meat is marinated in a flavour

punch of a marinade that combines miso and loads of Indian spices.

A signature of my cooking approach is that you can put big flavours

with big flavours, and something quite extraordinary happens when

you do. It’s a global sandwich in its outlook, but it’s not

complicated or hard to understand – it’s a fried chicken sandwich,

but just a very, very loud one.

Between jobs at Innocent Drinks and food marketing at Harrods, I

took a year off to go travelling on a sort of culinary pilgrimage.

I spent time in America, in Europe and Southeast Asia. It was a

year-long adventure where I ate my way around the world. When I

travel, I do it with the intention of seeking something, and

discovering food producers that create a taste of the place.

Wherever you’re travelling, do a little bit of research into what

the area is known for and how you can access it. Chances are,

you’ll find an adventurous, worldly and exciting community of food

creators wanting to share their story.

One of my favourite places to travel is Greece, because when you

drive through the islands – Crete in particular – there are streets

lined with people selling whatever they’ve been growing or making

in their gardens, whether it’s local honeys or olive oils. For me,

an incredible way of seeing a place and getting to know a place is

through its taste.

There are some incredible food producers in Portugal – the town

of Guimarães is full of them. It’s a historic place where many of

the roots of Portuguese cuisine stem from. There’s a store there

that sells street snacks from a mountain cave.

And then India is full of so many different cuisines; you should

get off the beaten track to find them. So, visit Mumbai and Delhi,

but also go to places like Hyderabad, Pondicherry and Lucknow.

These destinations are even more exciting for me, because they’re

not as visited but they have completely unique culinary heritages.

Everyone has their own completely unique culinary story, and

it’s something that can be, and should be, added to. Look back at

your own family history and put that into your kitchen, and combine

it with what you experience. There is a wonderful joy in bringing

your travels into your kitchen and engaging with diasporic

communities wherever you live. Get out there and taste everything.

Mother Tongue: Flavours of a Second Generation (Fourth

Estate) is available from bookshop.org for £26.

Main photo credit: Matt Russell