An all-female rodeo in Arizona shines a spotlight on the historically overlooked women of the west. Zoey Goto meets America’s modern cowgirls

07 November, 2023

Have

you ever wondered what the world would look like with women

at the helm? I often have, and it was this curiosity that enticed

me to a rural patch of Arizona – not much more than a corrugated metal

barn and a few dusty paddocks by the roadside, really. Because

here, a matriarchal microsystem has sprung forth from the desert,

and there’s a new sheriff in town.

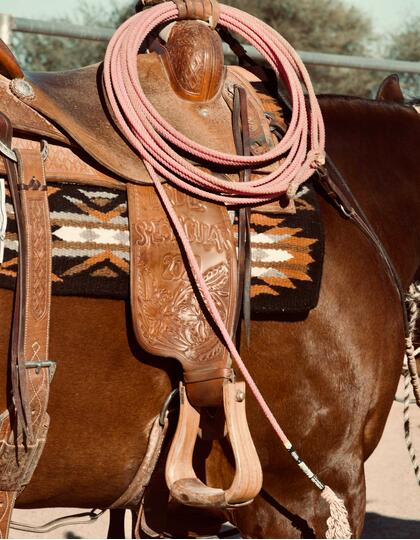

She enters the floodlit stadium riding atop a handsome chestnut

horse, arm protectively cradling a grandkid who sits buoyantly up

front on her engraved leather saddle. Tammy Pate, founder of the

Art of the Cowgirl festival, is here to talk to the crowd lining

the creaky grandstand benches about running a thriving cattle ranch

while raising a family. You can bet your bottom dollar it’s the

first time this topic has been aired at a rodeo.

Despite a long legacy of tenacious cowgirl folk heroes,

including sharpshooter Annie Oakley, who stole the limelight at

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, sixtysomething bucking bronco

grandma Jan Youren, and the lesser-known Sue Pirtie Hayes, who was

still snapping up trophies as a competitive bareback bull rider

while eight months pregnant, women have more commonly been pushed

to the margins of the rodeo scene.

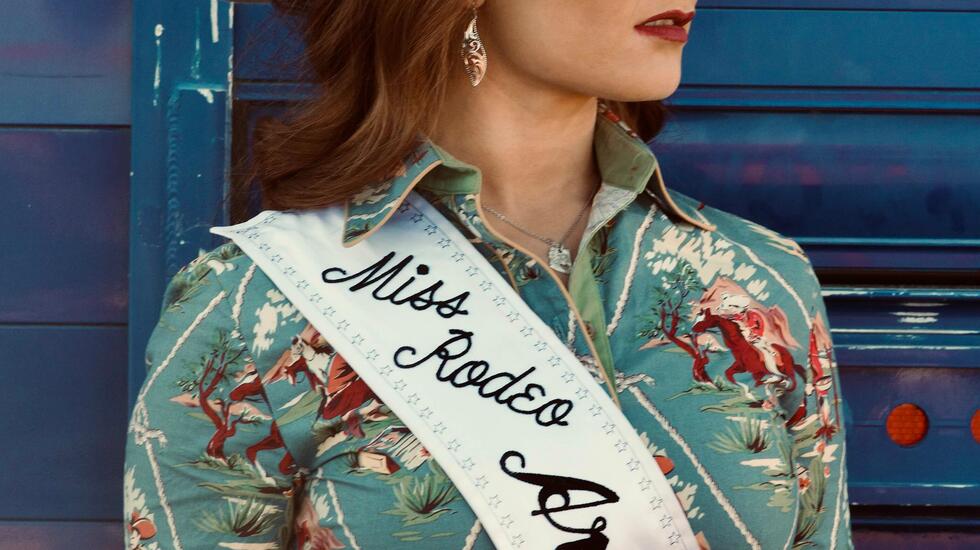

Small wins were gained when the Women’s Professional Rodeo

Association formed in 1948, after cowgirl athletes grew tired of

being reduced to sparkly beauty pageant hopefuls, or vying for

trinket prizes such as cigarette cases in lieu of the hard cash

splashed on their male counterparts, but, overall, this most

American of sporting events remained cloaked under a veil of

machismo. Fast forward to the present day and the limited options

on the traditional rodeo circuit allow females to compete in just

two categories: breakaway roping, in which riders lasso a

stampeding calf, and barrel racing, a fast and furious,

heart-thumping display of equestrian skill.

Bucking this culture, the Art of the Cowgirl is one of just a

handful of championships taking place across the US where “women

can participate in anything”, Pate explains, joining me at the

clanking steel bars of the ringside, just as the loudspeaker

crackles abruptly to life, announcing the next event. A chaos of

bewildered-looking calves is let loose into the arena, then

shuffled neatly like a pack of playing cards into a pen by a couple

of tag-teaming cowgirls. The air is thick with whoops, hollers and

the earthy smell of barn animals, as the crowd, in wide-brimmed

hats, squeezes thigh-to-thigh onto spectator benches.

The west has always been filled with strong women, but they’re now getting their stories heard

Having toyed with the idea of creating an all-female rodeo for

over a decade, it took turning 50 to spur Pate into action. Raised

on horseback in Montana, with a grandmother who could break a horse

with the ease of baking a pie, Pate’s mission was to celebrate the

unsung women of the west, roping into the spotlight not only the

daredevil cowgirls but also the silversmiths, braiders, saddlers

and bootmakers who toil behind the scenes.

“I really wanted to give back and empower these women,” Pate

says, her soft voice barely audible above the muffled thunder of

hooves. Now in its fifth year, the Art of the Cowgirl is a five-day

affair held each January in the small town of Queen Creek, less

than an hour’s drive from the urban buzz of Phoenix or the polished

marble lobbies of Scottsdale’s ultra-luxe resorts.

The Art of the Cowgirl forms part of a broader focus on cowgirl

culture currently emerging in Arizona. Dude ranches including the

White Stallion and Tombstone Monument now offer female-focused

packages, while renowned horsewoman Lori Bridwell runs a cowgirl

college teaching participants the time-honoured skills of riding,

roping and rounding up cattle. Once a year, the

Smithsonian-affiliated Desert Caballeros Western Museum decks its

walls with artworks highlighting western women’s voices and

perspectives for their celebrated Cowgirl Up! exhibition. “The west

has always been filled with strong women, but they’re now getting

their stories heard,” Pate reflects.

Back at the sage-scented desert and rusty barns of the Art of

the Cowgirl, the rootsy line-up features not only rough-and-tumble

drill team displays and the breakneck cattle-branding finals, but

also demonstrations with a distinctively holistic flavour. On my

debut rodeo day, I stumble across an equine therapy workshop. In

the centre of the paddock, a cowgirl stands bathed in soul-warming

sunshine, eyes closed and hand on heart, in silent communion with

the horse standing amiably by her side.

I am relieved to be welcomed with tassel-fringed open arms at

the rodeo, having quietly wondered if the real-deal ranchers would

see straight through my hastily brought Stetson hat and Texas

boots, my English accent marking me out as a cultural trespasser.

It’s this inclusive vibe that her festival strives for, Pate says.

“When I was dreaming of a women’s rodeo, this is exactly what I

envisioned,” she enthuses, as, in a moment of pure Americana, a

dazzling cowgirl gallops into the arena to the soundtrack of The

Star-Spangled Banner, a bedsheet-sized flag fluttering in the

breeze. The audience rises to its feet in unison. Eyes filled with

tears, Pate pauses for a beat before continuing: “My wish was

always to create a place that felt safe and inspiring to uplift our

community.”

Another example of this rodeo’s nurturing ethos is the Art of

the Cowgirl mentoring scheme, where master horsewomen and

craftspeople pass the old west baton down to the next generation. I

head across the fair, passing the billowing smoke of a campfire

gathering, beef tips in gravy simmering in a cast iron pot like a

technicolour scene from frontier flick The Wild Bunch. A woman clad

in double denim, the fringe of her flamboyant leather chaps

shimmying in the wind, schools a teenager in the art of lassoing in

front of a faded Pepsi truck, while, nearby, someone strums the

melodic bars of an old country tune on a guitar.

Framed by stalls trading tufty Aztec rugs and handcrafted

leather boots selling for around £8,000 a pop, I find Audre

Etsitty, a Navajo cowgirl who was awarded a week-long Art of the

Cowgirl fellowship, apprenticing under a world champion breakaway

roper in Texas. “I grew up on a reservation in Rough Rock, Arizona,

raised in a household where my grandfather was a traditional healer

and a first-generation cowboy,” the mother of three explains, her

youngest child toddling nearby. At the tender age of nine, Etsitty

swung into the saddle of junior rodeo and now competes on the

Indian rodeo circuit. “It’s a pretty big deal and culminates in Las

Vegas with the Indian National Finals Rodeo, where all tribal

nations in the US congregate.”

Etsitty’s heritage provides her with a particular slant on the

role of women in rodeo, she feels. “My Native American community

honours the matriarchy, so I haven’t grown up with the view that

rodeo culture is necessarily male-dominated. I guess I’ve always

seen it as women calling the shots.” Readjusting her turquoise

satin necktie, she’s quick to add that gnarly danger is ever

present at the rodeo and shouldn’t be taken lightly. “There’s

always a risk of injury with horses. I was at a barrel racing

jackpot where a lady was crushed to death by a horse. The risks are

serious,” Etsitty warns, before scooping up her daughter and

heading off to take her seat on a panel discussion about sisterhood

and mentorship.

Glancing at the rolling horizon, I double-take with astonishment

as it appears that a girl standing on two horses is stampeding

towards me. On closer inspection, a girl standing on two horses is

stampeding towards me. Kicking up dirt, Piper Yule, a rising young

gun of America’s rodeo scene, eases the neighing mares to a halt to

say howdy before careering into the main arena for her grand finale

performance. “I’ve made top five in pro rodeo for the last few

years,” she says proudly when I ask where she ranks in the rodeo

hierarchy. “But the goal is to hone my act so it’s less about smoke

and mirrors, more about reflecting my spirit as a cowgirl and my

horsemanship,” she adds.

Just 12 years old, Yule is a fifth-generation cowgirl from the

hardscrabble land of Southern Alberta, Canada. Her death-defying

show has become the star act at big-ticket rodeos across the US,

where, sequin jumpsuit glittering like a twirling disco ball, she

vaults on and off her galloping steeds and hangs off the side of

the saddle at bewildering right angles, occasionally clutching a

blazing firework just to crank up the already palpable tension.

Yule is known as a trick rider, the show ponies of the rodeo who

combine acrobatic horseback stunts with the old-school spectacle of

a big top circus act.

Today, she’s straddling the fine line between entertainment and

peril with a Roman riding show, muddy plimsolls planted on the

backs of a pair of galloping horses as they lap the sandy arena. At

one point, I find myself clenching my jaw, like an anxious parent

watching from the sidelines, as Yule precariously rides her

mustangs over a row of flaming torches. But, with the flick of a

long braid, they clear the roaring fires with flair, meeting me at

the backstage paddock where the horses, still snorting from the

adrenaline-fuelled display, will cool down.

“I feel the Art of the Cowgirl is helping me grow as a cowgirl,”

Yule says, once she’s caught her breath. “No matter your

background, you’re welcomed here and that makes it a really loving

rodeo,” she says, her championship belt buckle catching a ray of

golden sunset.

That evening, driving away from the rodeo through the stark

desert landscape, the soft glow of gas stations now seems to offer

an outpost of kindness. I’ve seen a glimpse of what life could be

and it is truly pioneering.